About Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is very common. It usually starts in infants from 3-6 months and is generally a disease of small children but may occur for the first time at any age. It is closely associated with atopic diseases such as asthma, hay fever and food allergy. These atopic disorders run in families but inheritance is not predictable. IgE sensitisation is present in about 80% of patients with atopic dermatitis and may present in young children with food allergies or acute allergic urticaria due to relevant exposures, such as contact with latex or taking antibiotics. About 20-40% of patients with atopic dermatitis have a genetic mutation of the gene encoding filaggrin in the stratum corneum, which results in impaired barrier function of the skin. This may, in turn, promote sensitisation by facilitating absorption of allergens through the skin, leading to ongoing inflammation and allergic airways disease.

Atopic dermatitis is very common. It usually starts in infants from 3-6 months and is generally a disease of small children but may occur for the first time at any age. It is closely associated with atopic diseases such as asthma, hay fever and food allergy. These atopic disorders run in families but inheritance is not predictable. IgE sensitisation is present in about 80% of patients with atopic dermatitis and may present in young children with food allergies or acute allergic urticaria due to relevant exposures, such as contact with latex or taking antibiotics. About 20-40% of patients with atopic dermatitis have a genetic mutation of the gene encoding filaggrin in the stratum corneum, which results in impaired barrier function of the skin. This may, in turn, promote sensitisation by facilitating absorption of allergens through the skin, leading to ongoing inflammation and allergic airways disease.

Diagnosis

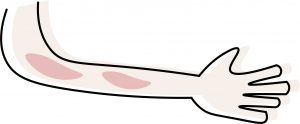

The key clinical features are itch, dryness and redness of skin. They are often accompanied by signs of damage secondary to scratching such as crusting, oozing and scabs. Crusted eczema is often sore due to excoriation and secondary bacterial infection. Blistering may suggest herpes simplex virus infection or impetigo. Atopic eczema usually starts on the cheeks and scalp in infants then adopts a limb flexural pattern in young children and adults. However, it may affect any part of the body and may occasionally be extensive enough to become erythrodermic. Relevant allergies should be suspected from the history and confirmed by skin prick testing or IgE-ImmunoCAP® testing on blood.

Management

Treatment is mainly supportive to relieve itch, improve skin dryness, reduce inflammation and treat infection. It is also important to avoid identifiable allergens and harsh environmental conditions, such as excessive exposure to irritants or sharp changes in temperature. Many children improve naturally with time so any risk from treatments that might cause long term damage should be minimized. The main pharmacological approaches are to improve barrier function of skin with regular applications of emollients, reduce inflammation with topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors and treat infection with systemic or topical antimicrobials. More severe atopic eczema might require ultraviolet phototherapy or short term systemic immunosuppressants. Education of patients and their carers is a very important part of management. Nurse-led clinics that offer practical demonstrations of topical therapies and provide a forum for discussion are usually very popular. Short admissions to hospital for concentrated skin care such as wet dressings can be very effective and may give the carers a much needed break from their responsibilities.

Coping

The condition may cause considerable distress to children and their families. It often results in sleep deprivation for the parents as well as the affected child who may develop behavioural disturbances. Treating children with sedating ‘classical’ antihistamines to help them sleep better may result in them being dopey the following day and should be discouraged as regular practice. Healthy members of the family may feel neglected by the amount of attention given to the affected child. Special diets and restrictions may have to be adopted by the whole household, resulting in atopic dermatitis becoming a ‘family disease’. Bedding and clothes often need to be changed and washed more frequently than usual. Special protective tunics and clothing may have to be worn, including ‘wet wraps’ in infants. Children with atopic dermatitis may not be able to join in activities in school and risk being marginalized. The young adult may have problems with hand dermatitis in occupations that involve frequent and repeated exposure to minor irritants, such as hairdressing or manufacturing. Older patients may experience dry skin associated with distressing itch that does not respond to antihistamines.