The lung is a very complex organ, designed to allow us to transfer oxygen from the air into our blood. To do so, it has a very delicate lining of cells, called the epithelium. The lung epithelium forms an intricate system of tiny linked air-spaces, and thus represents a very large surface area for the transfer of oxygen – it is estimated that your lung epithelium has a surface area the same size as a tennis court!

The epithelium releases IL-33 when it is damaged

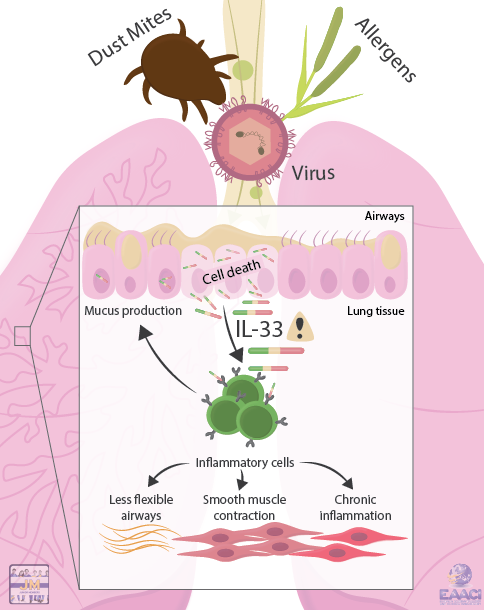

As well as effectively transferring oxygen to your blood, the lung epithelium can also detect and respond to potentially harmful particles and microbes in the inhaled air. When the lung epithelium encounters allergens, bacteria, fungi, viruses and noxious chemicals (for example in diesel smoke) it can release the immune system messenger molecule “IL-33”.

IL-33 is stored within epithelial cells and is only released when epithelial cells are killed. It is therefore a sensitive measure of epithelial damage. IL-33 can then act on a whole range of immune system cells located nearby, activating them and causing inflammation in the lung.

By being such a powerful inflammatory signal, release of IL-33 in the lung can lead to allergy and the development of asthma. The importance of IL-33 is supported by the findings that larger amounts of IL-33 are detected in the lungs of people with asthma, while people who have mutations in the gene for IL-33 have an increased risk of developing asthma. Finally, in mice, blocking the IL-33 pathway results in reduced pathology in models of asthma. Therefore, IL-33 appears to be an important factor in the development of asthma.

Serious viral lung infections can lead to the development of asthma

Another major risk factor for the development of asthma is serious respiratory viral infections in early life. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a common virus which infects lung epithelial cells. By the time they reach 2 years old nearly all infants have been infected with RSV, but in a minority of infants it causes “bronchiolitis”, a serious disease which requires hospitalisation. RSV bronchiolitis at a young age increases the risk of developing asthma, and recent work indicates that this may also be due to release of IL-33. In animal models of RSV infection, blocking the IL-33 signal also blocked the development of allergic and asthmatic responses in later life, with the potential for this strategy to be developed in humans.

New medicines to block epithelial responses could treat or prevent asthma

Clinical trials are currently underway to investigate whether blocking IL-33 could be an effective treatment for human asthma. Furthermore, current work indicates that by preventing the release of IL-33 in early life, interventions could prevent the development of asthma in the first place. It now seems clear that the lung epithelium, and epithelial release of IL-33, is central to the development of lung diseases such as asthma – if we can work out how the epithelium detects and responds to stimuli, we may be able to design a range of new treatments for serious diseases of the lung.

Read more on: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30734382

EAACI blog initiative

Author: Kristina Johansson studied IL-33 in asthma immunology during her PhD at Krefting Research Centre at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. By the end of 2018, she joined the groups of Dr. Mark Ansel and Dr. Prescott Woodruff at the University of California in San Francisco, United States, to continue Postdoctoral studies of non-coding RNAs in asthma, which includes signaling pathways related to IL-33.

Author: Kristina Johansson studied IL-33 in asthma immunology during her PhD at Krefting Research Centre at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. By the end of 2018, she joined the groups of Dr. Mark Ansel and Dr. Prescott Woodruff at the University of California in San Francisco, United States, to continue Postdoctoral studies of non-coding RNAs in asthma, which includes signaling pathways related to IL-33.

Mentor: Dr. Henry McSorley (Chancellor’s Fellow

Centre for Inflammation Research, University of Edinburgh) in the context of the EAACI Junior Member Mentorship Programme.