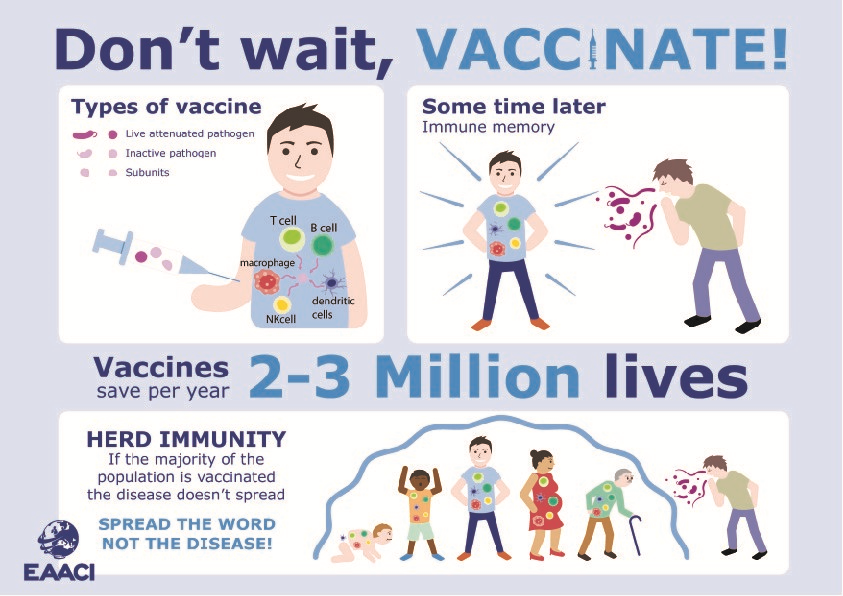

Vaccines are estimated to save 2-3 million lives each year. They have successfully eradicated smallpox, and greatly reduced the incidence of polio, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, mumps, rubella and measles. Licensed vaccines are currently available to prevent over 30 different infectious diseases.

How does vaccination work?

The aim of vaccination is to trigger a protective immune response to a specific pathogen without the risk of getting the disease. Vaccines initially induce an innate immune response, and then a pathogen-specific adaptive immunity.

Innate immunity is the first line of defence against an infection. It is established within a few hours after the pathogen has entered the body.

Adaptive immunity provides a second line of defence at a later stage of the infection, and is characterised by specific cells and antibodies recognizing the pathogen.

After the elimination of the pathogen, the adaptive immune system establishes an immune memory, which is the basis for the long-term protective effect of vaccination. Essentially, the vaccinated individual’s immune system will remember the pathogen and know how to fight it.

Who should get a vaccine?

From pre-birth to elderly age, we are constantly exposed to pathogenic infections that can be prevented via vaccination.

Vaccination of pregnant women can confer protection against pertussis or influenza (among others) to their new-borns. Infants and children are the age group best-served by current vaccination schedules. However, a proper programme of maternal immunization could help ease the busy immunization schedules of infants.

Adults in some countries receive scheduled vaccinations against tetanus and influenza, especially when they belong to a risk group, such as those working with potentially infected human samples.

An important target group for vaccination is the elderly population. They usually have special medical needs or an immunocompromised immune system, which makes them more susceptible to infections.

In addition, travellers of all ages should be vaccinated against the diseases they may find in the areas they travel to (cholera, malaria, dengue, hepatitis A and B, typhoid fever…).

Spread the word, not the disease!

Although vaccines are believed to just protect individuals who are vaccinated, they can also protect the unvaccinated population by reducing the rate of person-to-person transmission. This is called herd immunity.

For herd immunity to occur, it is required that a large proportion of the population i.e. 75-95% is vaccinated. Through this, unvaccinated individuals, such as very small babies and immunocompromised patients, can be protected by those in the population that are already vaccinated. When someone refuses to get a vaccine, this is not just posing a risk to themselves but putting the more susceptible individuals at a higher risk of infection.

Types of vaccines

There are different vaccine types depending on their mode of action and the level of protection they confer.

Live attenuated vaccines contain pathogens, usually viruses, that have been weakened or altered so that they cannot cause disease. Generally, they are produced through a series of in vitro cell cultures at low temperature, which select viruses that do not live well at body temperature. These vaccines provide long-term immunity after one or two doses. Vaccines against measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, influenza, herpes zoster, yellow fever and polio are included in this group. The only live attenuated bacterial vaccine in use is the one against tuberculosis.

Non-live vaccines are a heterogeneous group encompassing inactivated vaccines and subunit vaccines, such as protein, toxoid or virus-like particles (VLPs). Non-live vaccines generally have a good safety profile, even in immunocompromised individuals. However, their immunogenicity and duration of protection is lower than that of live attenuated vaccines. They may require several doses or adjuvants (added substances) to improve their immunogenicity. Examples of non-live vaccines are those against influenza, pertussis, hepatitis B, human papilloma virus, meningococcus, tetanus or diphtheria.

Perceived risks of vaccines

A very detailed review about the common perception of vaccines in Europe reported that the largest concern across all countries was vaccine safety.. Other concerns were the low likelihood of contracting vaccine- preventable diseases and the low severity of these diseases.

Despite the misinformation that has spread, vaccines are extremely safe, have little to no side-effects and are the most effective possible way of preventing millions of deaths.

So, be wise and immunise!

References

- Karafillakis E, Larson HJ. The benefit of the doubt or doubts over benefits? A systematic literature review of perceived risks of vaccines in European populations. Vaccine. 2017 Sep 5;35(37):4840-4850. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.061.

- Rappuoli R, Mandl CW, Black S, De Gregorio E. Vaccines for the twenty-first century society. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011 Nov 4;11(12):865-72. doi: 10.1038/nri3085.

- Vetter V, Denizer G, Friedland LR, Krishnan J, Shapiro M. Understanding modern-day vaccines: what you need to know. Ann Med. 2018 Mar;50(2):110-120. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2017.1407035.

EAACI blog initiative

Author: Cristina Gomez Casado (San Pablo-CEU University, Madrid, Spain).

Author: Cristina Gomez Casado (San Pablo-CEU University, Madrid, Spain).

Cristina Gomez-Casado is a postdoctoral researcher at the group of Allergy and Inflammation headed by Professor Domingo Barber in Madrid, Spain. She is currently involved in several projects that characterise mucosal barriers and systemic biomarkers in severe allergic phenotypes that do not respond to treatment. Her aim is to develop safe and effective therapeutic approaches to treat these patients. She completed her PhD on peach and kiwi allergy at the Technical University of Madrid, Spain, and enjoyed a postdoctoral fellow stay in Mucosal Immunology at Lund University, Sweden.

Cristina is member of the Immunology section board 2019/2021.

Senior author: Eva Untersmayr (Institute of Pathophysiology and Allergy Research, Medical University of Vienna, Austria). Mentor of Cristina in the context of the EAACI Junior Member Mentorship Programme 2014/2015 and chair of the Immunology section.