Together with our partners worldwide, we here at the Max-Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in Berlin aim to understand in detail a promising therapy for food allergy, called oral immunotherapy, which re-instructs the immune system to tolerate food again.

Food allergy has a significant impact on the quality of life of affected patients and can lead to life-threatening adverse immunological reactions to food within our body.

What is oral immunotherapy?

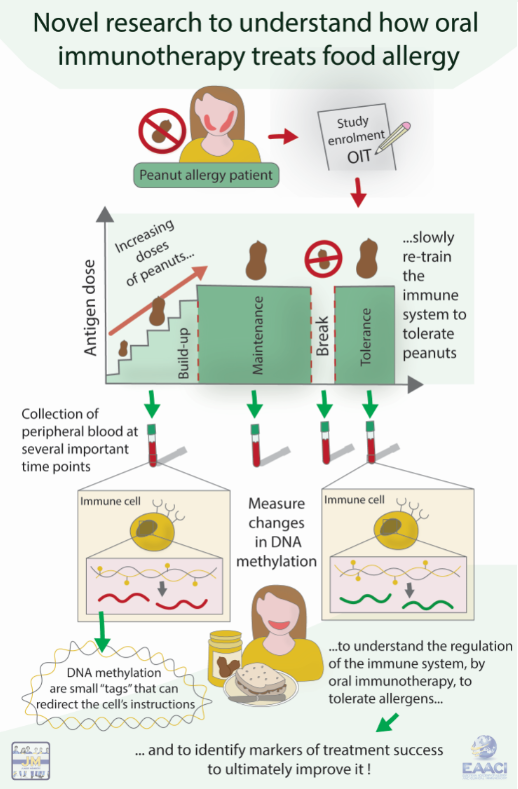

Oral immunotherapy is currently the only available curative treatment for food allergy, which is performed in specialised centres worldwide. It helps patients to overcome their allergies by slowly re-educating the immune system to change its response to food. Patients receive very small doses of allergens, such as peanut, which they consume for example in a pudding. Over time the amount of peanut inside the pudding is very slowly increased. By this procedure the immune system is taught to tolerate the allergen until patients are safely eating larger amounts of peanut without having a reaction.

How does oral immunotherapy work?

Our main focus is to understand how this therapy works. One process contributing to the re-education of the immune system is called DNA methylation. DNA can be considered as the cookbook for the human body, where all recipes (genes) are contained. All genes together (our genome) contain the information to form our body and to determine the function of each cell. DNA methylation is like a tag that attaches itself to our DNA. It can be considered like an additional note added to the cookbook. As DNA instructs the cell to perform certain actions, DNA methylation can change how the instructions are read, by removing a word and changing the meaning of a sentence. Previous work by another team of scientists in America has already shown that DNA methylation is involved in how oral immunotherapy can redirect the immune system to tolerate allergens. We now want to measure DNA methylation or the additional notes in the cookbook in a broader approach.

What are we doing to better understand how oral immunotherapy works?

Working with patient samples and data from a completed oral peanut immunotherapy trial study, I am measuring DNA methylation across the entire genome – I screen all recipes in the cookbook for additional information. We will measure at several time points for all patients. With this enormous amount of information, we expect to identify important sites in the DNA in which DNA methylation tags regulate the immune response during oral immunotherapy. In other words, we want to identify the main recipes that have to be changed to make food allergy treatment work.

Our goal: a safer and more efficient therapy for food allergy available for all patients!

At the moment there are still open questions associated with oral immunotherapy: what is the best treatment approach for each individual patient? How long do we have to give oral immunotherapy? When can a patient stop oral immunotherapy and still safely eat peanuts? We want to know what the best treatment strategy for each individual patient. Instead of a patient having to continue the therapy for years and still be unsure if he or she can safely eat peanuts, we look for markers to accurately tell each patient when it is safe to stop oral immunotherapy.

We expect our work to make this promising treatment for food allergies more effective and safer, in order to make it available for all food allergic patients.

EAACI blog initiative

Author: Sarah Ashley (Max-Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin, Germany). Sarah is a postdoctoral researcher in the group of Molecular genetics of chronic inflammation and allergic disease at MDC. She is interested in investigating the regulatory mechanisms of oral immunotherapy using genomic approaches. Sarah completed her PhD at the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia looking into genetic variants underpinning food allergy in the population-based HealthNuts study.

Author: Sarah Ashley (Max-Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin, Germany). Sarah is a postdoctoral researcher in the group of Molecular genetics of chronic inflammation and allergic disease at MDC. She is interested in investigating the regulatory mechanisms of oral immunotherapy using genomic approaches. Sarah completed her PhD at the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia looking into genetic variants underpinning food allergy in the population-based HealthNuts study.

Mentor: Eva Untersmayr (Institute of Pathophysiology and Allergy Research, Medical University of Vienna, Austria) in the context of the EAACI Junior Member Mentorship Programme.